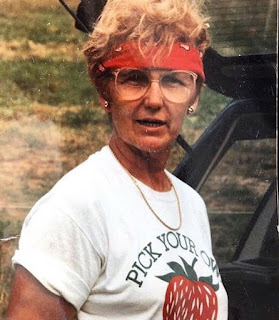

Strawberry Queen

In case you missed it on Historians Cooking the Past, I am posting my essay about my mom, Janice Weigand Shea, here.

If he had a tail, my father's would have been wagging. He would dash from wherever he was when the car approached the driveway and stand at the screen door, waiting. "Here she comes! All hail the Strawberry Queen!"

My mother emerged from the shadows into the flourescent light of the garage, smile and sneer competing on her face as she kicked off muddy construction boots. "Oh, please." Still, she liked the title. Returning from a 16-hour work day at the pick-your-own strawberry farm she managed with fields in Plainville, Hamden and North Haven, Connecticut, she'd kiss him hello and head to the shower, first peeling off dirt-encrusted jeans and a tee shirt with a big red strawberry on it.

My dad would bring her a cocktail or an icy glass of white wine and heat up whatever he had made for dinner. It was a reverse from business as usual, when he would return home from the office to find that my mom had a meal ready to go, table set and all. Post-work, she rarely ate much. I thought at the time that she was too exhausted for food. It was only years later that I realized she had already eaten -- usually with her friends and fellow strawberry farm queens, Adeline and Bertha. As an adult, it came as a surprise to me that my mom had favorite orders at fast food chains like Subway and Wendy's and deep nostalgia for the Italian subs and sausage and pepper grinders she ate at the farm. My father loathed fast food and was in his seventies before he acquiesced to their convenience factor, so my mother's stealth relationships with the drive-through jarred the idea I had of her, a stay-at-home parent without a solid identity outside of our family networks.

In fact, it took me a long time to understand that my mother's summer life as a successful and hard-working business manager was more than an opportunity to bring in much-needed cash. Friendships. A shared project. Being in charge. Temporary freedom from the roles of wife and mother that tended to define her. The money mattered, too, but not only because of its utility. I remember her fanning stacks of $20 bills and could almost see the mental math she was doing. It was her money to do with as she chose. Like her, I use my summer money to pay down debt, invest in needed house and car repairs. Like her, I make room for a few splurges, like a good facial moisturizer or a fancy shampoo. It is not so much that it is impossible to do these things during the "regular" year -- but my money is budgeted and spoken for. The earnings I bring in from extra work above and beyond my salary are mine to do with as I wish. I learned the pleasures of choice from watching my mom with her strawberry cash.

June 30, 2020

If he had a tail, my father's would have been wagging. He would dash from wherever he was when the car approached the driveway and stand at the screen door, waiting. "Here she comes! All hail the Strawberry Queen!"

My mother emerged from the shadows into the flourescent light of the garage, smile and sneer competing on her face as she kicked off muddy construction boots. "Oh, please." Still, she liked the title. Returning from a 16-hour work day at the pick-your-own strawberry farm she managed with fields in Plainville, Hamden and North Haven, Connecticut, she'd kiss him hello and head to the shower, first peeling off dirt-encrusted jeans and a tee shirt with a big red strawberry on it.

My dad would bring her a cocktail or an icy glass of white wine and heat up whatever he had made for dinner. It was a reverse from business as usual, when he would return home from the office to find that my mom had a meal ready to go, table set and all. Post-work, she rarely ate much. I thought at the time that she was too exhausted for food. It was only years later that I realized she had already eaten -- usually with her friends and fellow strawberry farm queens, Adeline and Bertha. As an adult, it came as a surprise to me that my mom had favorite orders at fast food chains like Subway and Wendy's and deep nostalgia for the Italian subs and sausage and pepper grinders she ate at the farm. My father loathed fast food and was in his seventies before he acquiesced to their convenience factor, so my mother's stealth relationships with the drive-through jarred the idea I had of her, a stay-at-home parent without a solid identity outside of our family networks.

In fact, it took me a long time to understand that my mother's summer life as a successful and hard-working business manager was more than an opportunity to bring in much-needed cash. Friendships. A shared project. Being in charge. Temporary freedom from the roles of wife and mother that tended to define her. The money mattered, too, but not only because of its utility. I remember her fanning stacks of $20 bills and could almost see the mental math she was doing. It was her money to do with as she chose. Like her, I use my summer money to pay down debt, invest in needed house and car repairs. Like her, I make room for a few splurges, like a good facial moisturizer or a fancy shampoo. It is not so much that it is impossible to do these things during the "regular" year -- but my money is budgeted and spoken for. The earnings I bring in from extra work above and beyond my salary are mine to do with as I wish. I learned the pleasures of choice from watching my mom with her strawberry cash.

After dinner and chatting with my dad on the porch, she moved to the kitchen table where she would reconcile accounts while he did the dishes. As a kid, the piles of cash always felt a little like she'd orchestrated a heist and was counting her loot. Although she had not gone to college, she had studied business in high school and worked in an insurance company when she graduated. My mom had a steel-trap brain and her focus was stunning to behold. While most people credited my dad -- the second person in his very large extended family to attend college and the first to go to law school -- with raising six smart kids, keen intelligence is our birthright from both parents. And my mother was methodical and meticulous -- if the box was off, she recounted from the beginning. She taught us how to do it as well. "You'll need to know this," she'd say, looking across at us over her glasses. Her daughters, she had already determined, had futures that involved needing to know things about money, about business, about accountability.

She'd be up at 5:00 AM on those June mornings. If you were working at the farm, which my sisters and I did from the time we were old enough, you would be up as well. Groggy, we'd drive by the fields as the sun rose to see where the irrigation was set up, if the scarecrows had done their jobs, and to find John, the farm manager, to figure out where the best berries were and what needed to be picked before it rotted in the fields. Customers arrived early, often before the 8:00 AM opening. My mother was a phenom of customer service. Her charm was rooted in authentic love for people, and as a mother of six, she had eyes and ears everywhere and an uncanny sense for where her attention was needed. She met all reasonable requests, put us to work picking berries for those too elderly or infirm to pick their own, handled complaints and kept a large staff in line. She trained us so well that I can still reel off the standard Pell Farms greeting without a second thought! (I know you're curious so I recorded it -- you can listen to it here.) She didn't put up with bullshit and she almost never took a day off -- strawberry season is short in New England. When we weren't working with her, we learned to get along without her.

By the nineties, the fields that once were filled with strawberries had been sold to developers. Pick your own fruit farms became part of a vanishing New England. My mother turned her attention from raising children to caring for her aging parents. Since she died two years ago, suddenly and very unexpectedly, learning to get along without her has been consuming in ways I didn't anticipate. I encounter her memory in the usual ways but also in the least likely places --- the taste of hot french fries from the drive-through, the call and response at a protest for BLM, a sparkly shirt on a rack that I know she would have liked. I am glad she didn't have to live through COVID-19. She would have hated all of this -- the lack of freedom to be with people, the worry for her loved ones, the possibility of contracting the virus, the realities of being cooped up in a three-room apartment with my father. Still, her absence has brought grief and betrayals within my family that run so deep I am not sure they will ever be reconciled. It has revealed all the ways she was the heart of us. Our queen.

Janice Shea was also very much her own person and strawberry season makes me think of my mother at her best. Since the day after she died, she's often made her presence known in the form of a cardinal. This is common enough. I like to think, though, that she chose that incarnation not only because she was a traditionalist at heart, but because the bright red plumes of the cardinal evoke the glorious strawberry.

Certo No-Cook Strawberry Jam

My mother was too busy during strawberry season to do much with strawberries other than slice them and eat them with cream or occasionally make strawberry shortcake. Honoring both that busy season and her strong legacy of friendship, here is fellow-editor and friend Stacey Zembrzycki's recipe for freezer strawberry jam.

Hull and crush (in layers) 2 cups strawberries. Mix with 4 cups of granulated sugar. Let stand 10 minutes.

Combine ¾ cup water with Certo Pectin Crystals in small saucepan. Bring to a boil on high cook; cook 1 minute, constantly stirring.

Add pectin mixture to fruit/sugar mixture and stir for 3 minutes.

Pour into clean containers, filling up to ¼ inch from rims. Cover with lids. Let stand at room temperature for 24 hours or until set. Refrigerate or freeze until ready to use. No need to sterilize jars!

Margo Shea learned her way around the kitchen with parents who loved to cook together and she treasures their well-loved, duct-taped copies of Joy of Cooking and Mastering the Art of French Cooking. She teaches public history at Salem State University and believes in the power of cooking and sharing food.

Comments

Post a Comment